As is so often the case, absence raises provocative and sometimes unresolvable questions. In this case, why are there so few Native Hawaiians at the University of Hawai‘i? What do the papers in the RASRL Collection tell us about the Hawaiian community? This post is a preliminary effort to address these questions.

Report of the Board of Regents to the Governor and Legislature, December, 1924

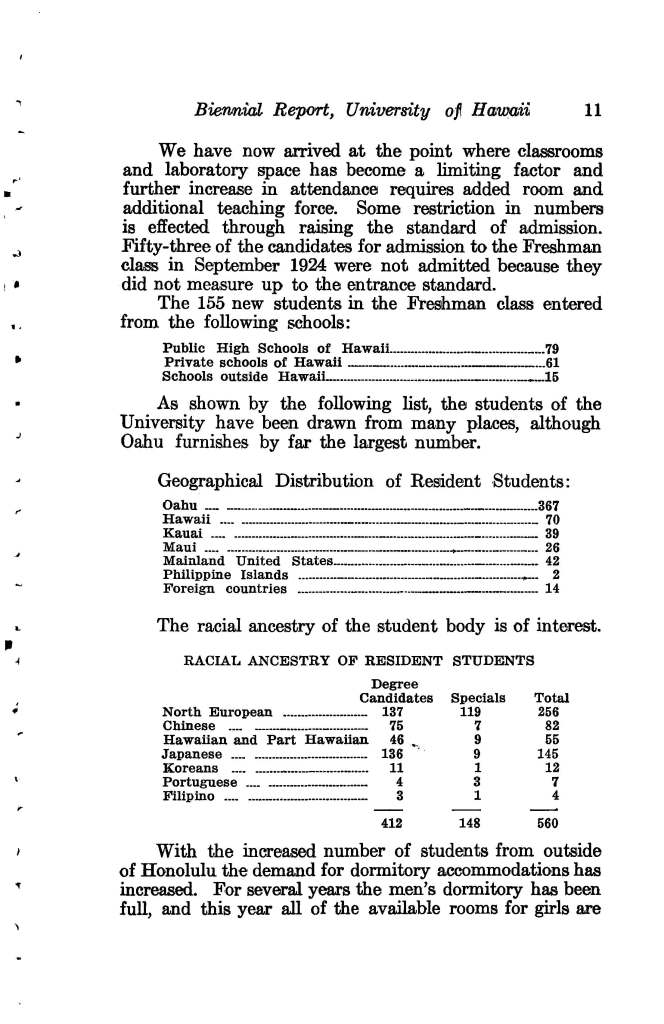

Native Hawaiians were enrolled in the University of Hawai‘i consistently for the two decades before World War II. During the first decade of the University’s existence, Native Hawaiians (including those classified as Hawaiian, “Part Hawaiian,” “Asiatic Hawaiian” or “Caucasian Hawaiian”) were a small but visible presence and their numbers on campus were roughly equivalent to their numbers in the general population. The University was inconsistent about how they kept and disseminated information about the ethnicity of the student body. However, two reports made to the Territorial Legislature tell us that during the 1924-25 school year, fifty-five of the 560 students at UH were Hawaiian or part-Hawaiian. Two years later, eighty-five of 879 students were Hawaiian, an increase in number but a decrease in the overall percentage of the student body. The RASRL papers contain some data compiled from a variety of sources. Although they are inconsistent and possibly not reliable, they show a similar pattern; some growth in the overall numbers but never rising to more than 15 percent of the student population. In the last year for which we have any information, 1942, the number of Hawaiian students on campus had dropped to seventy-seven out of 1,741 undergraduates. During these years, then, the percentage of Hawaiians in the UH student body dropped from about 10 percent to under 5 percent. (Data compiled from RASRL Student Papers A1979-0-43, “University of Hawaii”)

Why didn’t more Native Hawaiians attend the University of Hawai‘i? It is useful to keep in mind that post-secondary education was not common during this era, in Hawai‘i or in the US. Before World War II, not more than 15 percent of high school graduates went on to college and most of them were from middle- or upper-class families. Since Nisei and other second generation students described how important education was to their families, it is tempting to see those who chose not to attend college as not valuing education or being anti-intellectual. Following this line of thinking, we’re led to see Hawaiians through the lens of the dominant stereotypes of the era – fun loving, but not particularly bright; good natured, but trouble makers prone to criminality or laziness. Comparing Hawaiians to other local adolescents and young adults in this manner suggests that higher education was the only way to master a skill, learn a profession, or become a valuable member of the community. It also assumes that western education was more valuable or relevant to their lives.

Hawaiians did face barriers to attendance: preparation (the ability to pass the entrance exam or accumulate the necessary credits), financial (the ability to afford tuition and fees), and practical or cultural. Any or all of these issues may have offered more significant impediments to Hawaiian students. Daviana McGregor suggests that during the pre-war era, the majority of Hawaiians lived in rural areas of Hawai‘i, maintaining strong connections to the land and family. Hawaiians who moved to the cities – especially Honolulu – assimilated, but na kua‘aina (country folks) remained committed to Hawaiian traditions. Finishing secondary school was also a challenge for Hawaiians who lived in rural isolated villages. Describing life in Waipi‘o, Hawai‘i Island in the 1930s, McGregor says that in order to attend high school, children left the valley and traveled fifty miles to the nearest high school in Hilo. Those who left tended not to come back. “Usually, one of the children remained behind to care for the kuleana and to look after the old folks” (Daviana McGregor, Na Kua‘aina, p. 63).

McGregor also provides another clue that might inform our understanding of Kanaka Maoli at UH. Native Hawaiians were not a significant part of the plantation work force. They were skilled laborers, teachers, domestics servants, or earned a subsistence living fishing and growing crops. In other words, Hawaiians were not trying to escape the plantations like so many of their Asian American counter parts. A college education offered the promise of a better life for the Nisei, but this may not necessarily have been the case, even for middle-class Hawaiians. “In 1927 Hawaiians held 46 percent of executive-appointed government positions, 55 percent of clerical and other government jobs, and over half of the judgeships and elective offices. Through 1935 Hawaiians held almost one-third of the public service jobs and dominated law enforcement, although they made up only 15 percent of the population of the islands” (Na Kua‘aina, p. 44). In other words, Hawaiians may have seen college as an option, but not the only or even the best option. For the sons and daughters of immigrants, a college education was not just a ticket to the middle class; it was also a way of securing their status as Americans, full participants as US citizens. Kānaka Maoli may not have felt this pressure so acutely. Assimilation and conformity did not necessarily dominate their community values.

What does the RASRL Collection reveal about Hawaiians? Not as much as might be expected. Since the RASRL faculty and researchers did not compile or tabulate any meta-data about the collection we have no way of verifying how many Hawaiians were RASRL writers. Names are an imperfect signifier of ethnicity in Hawai‘i. Inter-marriage was a fairly common practice. Hawaiian students often carried the last name of a Haole or Chinese ancestor. A Japanese child raised by a Hawaiian family might take on the name of her hanai family. First names are even less helpful; a “Pualani” might be Haole, Portuguese, or Hawaiian. In some cases, students revealed their Hawaiian ancestry by discussing family genealogy or their participation in on-campus or local Hawaiian organizations. We’ve proceeded on the assumption that students who carried a Hawaiian last name were Hawaiian. We also assume that students who self-identify as Hawaiian in their writing were Hawaiian and that students who have the name of a well-known Hawaiian or hapa Haole family were probably Hawaiian as well.

We are also able to identify Hawaiian students in the RASRL Collection through coding that identified the ethnicity, gender, and other information of the writer. In some cases, papers by and about specific ethnic groups were filed in this way, making it easier for faculty and student researchers to find information about a specific group. We occasionally find folders marked “Hawaiian” which suggests (but does not guarantee) that all the papers were written by or about Native Hawaiian students.

The relatively small number of students on campus means that there are fewer papers that discussed Hawaiian families and communities. Hawaiian students seemed to be reluctant to talk about their families with as much candor as other students. Non-Hawaiian students whose work discussed the Hawaiian community often repeated stereotypes that provide no real insight other than to reveal the dogged persistence of negative representations of Hawaiian .

Although the RASRL Collection tells us very little about the Hawaiian community at large, it provides useful information about part-Hawaiian students and their families. The RASRL faculty frequently assigned biographical papers or had students complete assignments about their families. In these assignments, students who identified as part-Hawaiian (having one or more relatives born into or closely identified with the Hawaiian community) discuss their feelings about and responses to being from a mixed racial or cultural background. Although intermarriage was common in Hawai‘i, students often felt conflicted about their status or identity. Negative stereotypes about Hawaiians were commonly reiterated by students who felt pressure to conform to their Chinese or Haole family values.

Students express a range of emotions about their Hawaiian ancestry, from shame and embarrassment to pride. One writer who identified as Hawaiian-Danish said “I am unusually sensitive to the remarks and actions especially to foolish and unintelligent acts of the Hawaiian race, and some of these characteristics … have tended to make me feel ashamed for them …” (K. B., Glick Papers Box 2; “Social Control” folder).

In some cases the papers reflect the tension and hostility between ethnic communities and often the onus is on Hawaiians. They are caricatured as lazy, poor, or unreliable workers. “My parents hated the Hawaiians and protested against my constant association with them. Their idea of a young Hawaiian is a carelessly dressed person, lazily lounging around street corners with a ukulele in his hands” (“Chinese female (1920s)” Glick Papers Box 2).

Some students discuss close, even intimate relationships with Hawaiians – one Chinese girl was taken care of by Hawaiians in her plantation town while her parents worked. “I guess that it is because of my early contact with them that I have always had a liking for Hawaiians. I admire their simplicity and generosity. I have always been drawn to them. I mingle with them so much that I can almost be one of them” (“Interesting Cases” folder, Glick papers Box 2).

Sometimes we see Hawaiians reflected through the eyes and experience of a hanai child. One writer described her mother’s experience growing up with the grandmother who adopted and raised her. Interestingly, the writer says her mother was given up because her own mother didn’t want her, a common way of characterizing Hawaiian adoption practices. It’s difficult to know whether this writer knew that her mother wasn’t wanted or if she was parroting the common stereotype of Hawaiian women casually giving away their children. Nevertheless, she describes her family’s relationship with their Hawaiian relatives as kind and affectionate. “Everyone is fond of Hawaiian foods and Hawaiian music, and mother is at home with the Hawaiian language” (“Interesting Cases” folder, Glick Papers Box 2).

These examples don’t reflect the range of responses of part-Hawaiians students and it might be difficult to discern a pattern or draw consistent conclusions. The time period (pre- or post-war), class, and gender are all reflected in the work of the RASRL writers and shaped their responses and points of view. Further discussion (and posts) about Hawaiians will deal with how Hawaiians represented themselves in student life at the University of Hawai‘i.

Please visit our companion website Local Citing where we feature several community studies form the RASRL Collection in the Mapping the Territory exhibit.

Pingback: Transitional Communities: Pālama and Environs in the Late 1920s | Thinking Locally

Pingback: Maunalaha, a Study of an Urban Hawaiian Community | Thinking Locally