After December 7, 1941, the Sociology Department began to study the impact of the war with special funds allocated by UH’s Board of Regents (University of Hawaii Bulletin, The Report of the President for Fiscal Year July 1, 1942 to June 30, 1943, pp. 6-7).

After December 7, 1941, the Sociology Department began to study the impact of the war with special funds allocated by UH’s Board of Regents (University of Hawaii Bulletin, The Report of the President for Fiscal Year July 1, 1942 to June 30, 1943, pp. 6-7).

For Andrew Lind and Bernhard Hormann, UH sociologists, the goal of their wartime work was not to “keep up morale,” which suggested the use of propaganda, but to measure it.

By morale we mean the essentially human aspect of any collective activity, that is, the fundamental attitudes of the people engaged together in some enterprise, toward that enterprise and their place in it. We differentiate from the courage and stamina of the individual in his private activities and from the emotional excitement of the passing crowd. As we see it, morale is the central interest of the sociologist when he studies any kind of collective action, for every such action has a morale problem (“The Study of Morale by the War Research Laboratory: University of Hawaii,” undated, RASRL War Research Lab, Box 1, Folder 22, p. 2).

While conducting public opinion polls was tempting for the faculty (and was done at times),

[t]he very act of asking a person about his opinion, attitude or feeling on any matter involves an exchange of attitudes between the questioner and his subject. The more the questions touch crucial issues or seek to get at fundamental and stable attitudes, the more disturbing the interview situation per se may become. It would be senseless for a haole to ask a local Japanese how he felt about the war, because the Japanese would immediately think: “What is this haole trying to get out of me? I had better be on my guard.” If he is intelligent, he may reason to himself: “If I show great enthusiasm for the American war effort, this haole will certainly not believe me sincere. If I am reserved, he may think me disloyal.” Likewise, if a Japanese interviewer sets about questioning a fellow-Japanese, he will be considered by the latter a “dog,” that is, a person who is spying … (p. 6).

So, how could the faculty measure morale?

We feel that there are two ways open to us. One is to get the intimate and frank statements of persons; the other is to get the spontaneous reactions of people [emphasis in original] (p. 8).

Because intimate and frank conversations happen between friends, the faculty felt that this was the best way to “poll” the feelings and attitudes of a group.

Getting information from Japanese by Japanese is more representative than getting that information from others. Persons who do not know intimately one Japanese hardly have the right to speak about Japanese loyalty or Japanese characteristics …(p. 9).

And who would be in the best position to collect data?

In our capacity as teachers we also occasionally receive the confidences of our students. Our position is after all a professional one like that of the physician and pastor. It is because we do get close to our students through teaching that we sociologists feel that teaching is a vital part of our work as sociologists (p. 9).

RASRL writers’ morale diaries are vivid reports of the impact of the War on Hawaii’s civilians. This data – highly specific, anecdotal, without analysis, barely contextualized beyond a date and location in which events and conversations were observed and recorded – became the content of the reports Lind and Hormann asked their students to keep.

Because students were instructed to report on what people were talking about, the morale diaries frequently mention larger events, such as the lifting of the blackout in May 1944; the explosion at Pearl Harbor on May 21, 1944; Masao Akiyama’s controversial refusal to be inducted into the US Army; the Draft and furloughs for local soldiers; and the chronic housing shortage. But a greater value of the diaries are the detailed accounts of what RASRL writers experienced and witnessed in the first two years of the war, what they heard while waiting at bus stops or as they rode buses, and their “intimate and frank” conversations with friends.

Because the majority of the writers were Japanese Americans, the diaries are thick with the reactions of other Hawai‘i residents to them and their families. In spite of the faculty’s confidence in morale students’ ability to directly garner candid responses from informants, many students, as they rode buses and stood in lines, leaned in closer on others’ conversations to “shamelessly listen” (No. 334, “The Effect of the War on Race Relations,” undated, Folder 8: Student Journals 315-338). One Japanese American writer expressed the difficulties he encountered in getting other Japanese to open up: “a slip of the tongue may send [the interviewee] to “Sunajima” (Sand Island) for the duration of the war.” This writer also added, “in spite of pre-interview explanations, the interviewer’s motives are not completely trusted” (No. 340a, morale diary, 4/15/44, Folder 9: Student Journal 339-355). Several writers noted that the Japanese knew they were being carefully watched not only by the F.B.I. but others, including those in their own community.

Japanese not only felt the pressure to hide their Japanese-ness but also to proclaim their American-ness. Issei enrolled in English classes and were encouraged by their children and urged in declarations on public posters to “Speak American” and “Do Not Speak the Language of the Enemy.” Women put away their kimono and geta and donned western dresses and, for many, uncomfortable western shoes. They became hyper-conscious about being Japanese:

They limit their home visits to as few persons as possible, they isolate themselves on buses for fear of meeting their friends and hence, have to commute [sic] in their native tongue and being condemned for “un-Americanism” (No. 316, “The Japanese, the Filipinos, the War,” 9/4/43, Folder 8: Student Journals 315-338).

While on the bus, this same writer witnessed two Issei seated together who avoided talking during the thirty-minute bus ride, while two Chinese women in Chinese dress sat in front and conversed in their native language at full volume. When one of the Japanese said goodbye in Japanese and bowed to her friend when she left the bus, “Almost everyone stared and looked with hatred at the couple!”

Even young Japanese Americans often couldn’t do anything right. Walking down the street with their gas masks, the writer and her friends were taunted by boys who asked if they had heard from Tojo on their secret radios that Japan was going to bomb Hawai‘i. Showing up at a theater without their gas masks, these same women overheard “women in the military” commenting that not carrying gas masks was a sign of disrespect especially since the US was spending money to provide civilians with masks (No. 328, untitled, undated, Folder 8: Student Journals 315-338).

Complaints about inadequate bus service and consequent over-crowding are part of a dominant narrative about wartime Honolulu. But the crowding did make it easier for morale writers to easily eavesdrop on conversations. They heard about food rationing on the continent and complaints about Honolulu’s black market for meat; the unfairness of the Draft, with Haole and Chinese being deferred while Japanese and Filipinos were called up; and derogatory or pitying comments about those classified as “4-F,” men of draft age found unfit for military service.

The crowding also put young Japanese women in the midst of large numbers of men, some of whom they had grown up being warned about:

We dreaded the sight of [Filipino] men with high waist pants that came up to the chest, and with their colorful suspenders, with their odious chewing tobacco, and a much too sweet perfume odor. Any girl who passes these men was sure to receive some kind of an attention – either “ss-tt-st” or “Hello.” Aboard buses they spoke in their native tongue so loudly that they have acquired the name “peck-peck” (No. 316).

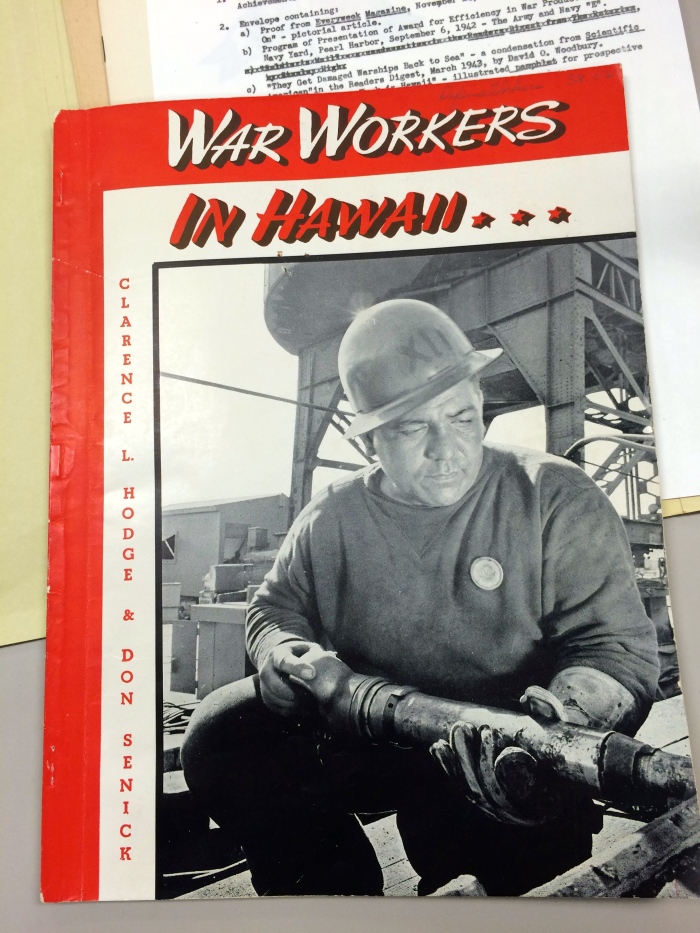

HWRD Collection, Defense Workers 38.02

Defense workers were objects of curiosity as well as disdain. These workers were often characterized as “draft dodgers,” although many were highly skilled workers needed at the Pearl Harbor shipyard. Most RASRL writers had never seen or come in contact with working class Whites before, a very different kind of Haole. One writer said she had met some nice ones but most, she felt, were from low, ignorant classes. Local writers were particularly sensitive to defense workers’ complaints about Honolulu:

Sure, they come from the mainland but many of them come from places really in the sticks – more hick town than Honolulu – why should they complain about Honolulu – they may have come from worst places (No. 334a, morale diary, undated, Folder 8: Student Journals Fall 1943).

Morale writers also reported slights and humiliations that occurred on buses: Haole men refusing to yield seats to older Japanese women but immediately relinquishing their seats to Haole women; a Haole man being chided for giving his seat to an Issei (No. 325, “The Effect of War on Race Relations, undated, Folder 8: Student Journals 315-338). Another time, a writer’s friend offered his seat to an old Japanese woman who then held the seat and called out to her husband to take it. The soldiers watching said, “Gosh! Gentlemen before ladies in this God forsaken country.” The writer admitted that even she and her friend were surprised to see this woman’s deference to her husband (No. 334).

Morale writers readily shared gossip and even second- and third-hand rumors about violent confrontations. More than one writer reported an account, which may have been apocryphal, of WACs who complained about standing while “dark people” (Hawaiian or Hawaiian-Chinese) had seats. One local girl allegedly jumped to her feet and slapped the WAC to the floor (No. 320a, morale diary, 4/25/44, Folder 8: Student Journals 315-338). Another passed on a story about Marines stopping a bus in Honoka‘a and trying to pull an elderly alien Japanese off the bus. A soldier and passengers stepped in to protect the man (No. 326).

One writer passed on a story she’d heard from a White sailor about a fight between Blacks and Whites at a boxing match.

After the incident, every white sailor at the receiving station was issued several rounds of ammunition to protect himself from the negroes, and guards were placed all around the barracks. Later in the week, practically all of the negroes were taken up to some remote place and fenced in with marine guards watching who were told to shoot to kill (No. 286, morale diary, 1944, Folder 6: Student Journals 275-294).

Such reports or rumors fed into writers’ wariness about African Americans, another group with whom local students had had little or no contact before the War.

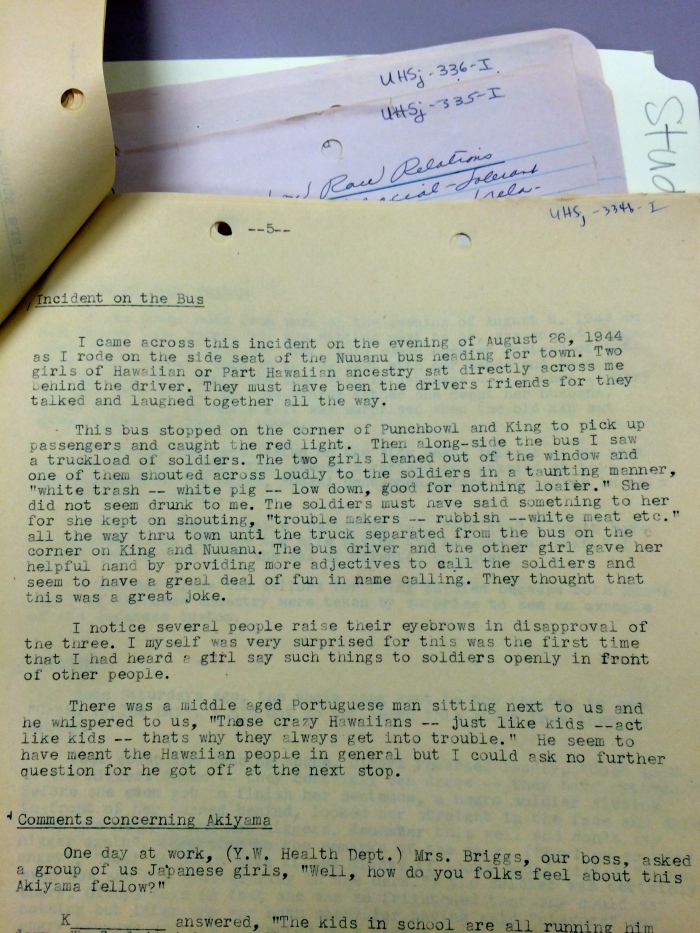

Some did witness altercations: a drunk Filipino railing at three Chinese girls on the bus whom he mistook for Japanese (No. 315, “Effect of War on Race Relations,” Folder 8: Student Journals 315-338). No. 320 reported a fight between Marines and defense workers in front of a store near the writer’s home (morale diary, 5/26/44, Folder 8: Student Journals 315-338). No. 334 (above image) recounted the provocative behavior toward soldiers of two girls who were safely ensconced on the bus.

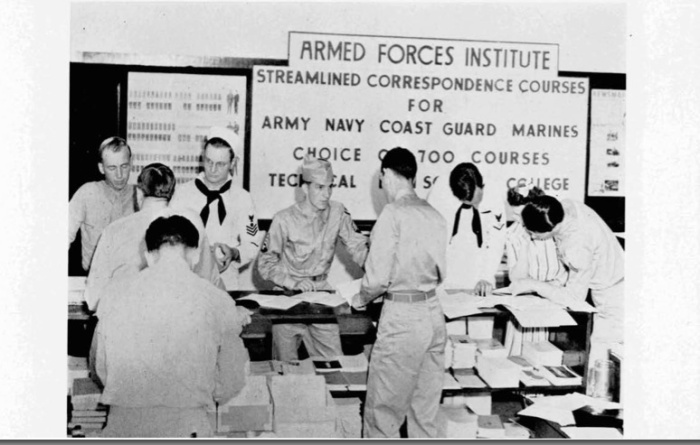

Like everyone else in Hawai‘i, UH students, the majority of whom were women, did their part for the war effort. They sold war bonds, worked at the Red Cross, and used their Wednesdays, after UH officially cancelled classes on that day of the week to replace workers who either had been drafted or who had taken more lucrative defense jobs (University of Hawaii Bulletin, The Report of the President, Vol. XXIII, No. 1, December 1943, p. 8). They worked at the cannery, in pine fields, staffed day care centers. The AWS (Associated Women Students) organized a drive to collect Christmas gifts for servicemen (Ka Palapala, University of Hawaii 1943, p. 31) and co-sponsored a campus Victory Workroom with the Junior Red Cross in which to make scrapbooks and valentines. A letter was included with each scrapbook that, in part, read:

The University of Hawaii sends greetings to you, men of the Service, with the hope that, though far from friends and loved ones, you may find in our Islands new acquaintances and true expressions of Aloha – friendship. Since the life of our university depends upon your defense of our Islands, the students of the University of Hawaii wish, through this gift, to express their appreciation of your sacrifices and your devotion to duty. On it is the rainbow, the University emblem, with its message of courage and faith in the future (pp. 31-32).

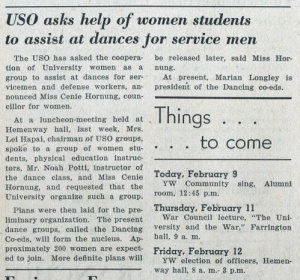

One of the persistent threads running throughout the RASRL writers’ papers before the War is the resistance Nisei women faced from their parents when it came to attending dances of any kind. The condemnation of dancing is only outmatched by their parents’ objection to interracial dating. Yet with the War and the arrival of troops – skewing the ratio of men to women from an estimated low of 100 or 150: 1 to a high of 350:1 – both dancing and eventually dating became activities that allowed local, and in particular, Japanese women to do their part in keeping up servicemen’s morale. In addition to attending dances sponsored by the AWS, other UH groups, and the Y, women students were recruited to attend USO dances. Hui Menehune, an organization sponsored by the USO, was created to make sure women attended dances. This group as well as the USO drew criticism, but one morale writer showed insight and offered a spirited defense:

The USO was the target of criticism lately, made by local personalities due to the fact that it had segregated the white from Negro soldiers by building another facility for the latter. Many blamed the USO for bringing on their racial prejudices to Hawaii, where it hadn’t existed before this. Only a naïve person would believe this to be true since we do have our share of discriminations [sic] and the like only it has been on a minor scale. The situation as created by the USO was an example of a major racial discrimination against an ethnic group which had never been antagonized heretofore. Future attitudes towards the negro are being formed today (No. 357a, “Club Organization and Its Relation to the Community (V),” undated, Folder 10: Student Journals 356-377).

Women students, especially those who lived in Hale Laulima, the on-campus dormitory that hosted dances for servicemen, were in a unique position to become acquainted with servicemen:

. . . women students were not greatly affected nor cared about servicemen until the first group of Signal Corps members arrived on the campus in March, 1941, to live at Atherton House and to take up special work here. At that time already, there was a noticeable decline in the number of men students – all having left with the VVV, drafted by the army, or employed in defense jobs. The girls at that time, being devoid of masculine attention, did not have very many dates and thus lived practically by themselves. However, with the coming of these men who would have classes with some of them, who ate in the same cafeteria, and who studied in the same library, blossoming friendships grew up. At first, though, the men were ignored – evidence of the old social conformity. However, as soon as they began to meet the girls, especially those living in dormitories, gradually this feeling of social conformity lessened (No. 364, “Major Changes I Have Observed in the Controls Exercised within the Various Ethnic Groups Since the War,” 1/19/43, Folder 10: Student Journals 356-377).

Students in sociology classes completed questionnaires asking them about their attitudes toward interracial dating, and several dozen morale diaries focused on this topic. Writers talked at length about their reasons for interracial dating; that is, dating servicemen. They were unequivocal in their assessment that dating was a way to show their patriotism and loyalty to the US and many as a way to demonstrate how they wanted their brothers in Shreveport and at Camp Shelby, who were likely as lonely as soldiers in Hawa‘’i, to be treated. For others the reasons were more prosaic: their boyfriends were away and the soldiers were “cute,” more polite and sophisticated than the local men. Some writers framed interracial dating as intercultural exchange and something that added to their own education: “girls learn new things from boys,” improve oral English, and add “color to ones’ personality” (No. 345 “Interracial Dating,” undated, Folder 9: Student Journals 339-355).

Some UH women assiduously avoided dating servicemen, especially writers who lived at home and were under the watchful eyes of relatives and neighbors. Others approved of it but didn’t themselves date even if they had opportunities to do so. A few crossed deeper into interracial territory:

. . . I think these servicemen and defense workers are very nice and interesting to go out with – better than any deadhead oriental boy. After associating with [servicemen, defense workers] I simply cannot bear oriental boys, they seem so unpolished, uncouth, and uninteresting compared to these haoles. I don’t care what my friends and parents say, I’m engaged to be married to a haole soldier and no one’s going to stop me (No. 341, “Interracial Dating,” 5/29/43 Folder 9: Student Journals 339-355).

This same student expressed a pessimism, one that might well have been shared by many Hawai‘i women during the war: “. . . sometimes when I think that these Japanese boys are not coming back, I think it’s better to grab a haole man and get married. Anyway, by the time the war is over haoles will be the only ones left.”

These brief writings, now archived as Student Journals, focused on hot button issues of the years of 1943 and 1944. In their diaries, writers shared rumors that circulated, described scenes they witnessed in the community, recorded fears expressed, and highlighted flashes of pride and courage that demonstrated the best of others and the RASRL writers and their families. To the faculty – and presumably to all those who had access to this data – what the RASRL writers provided was immeasurably important: “Public opinion is about the issues of the day … Morale, on the other hand, is about the very destiny of the society” (“The Study of Morale by the War Research Laboratory,” p. 5).

Please visit our companion website Local Citing where we feature several community studies form the RASRL Collection in the Mapping the Territory exhibit.

Pingback: Race and Gender in the Wartime Workplace | Thinking Locally

Pingback: Judith and George | Thinking Locally

Pingback: Maunalaha, a Study of an Urban Hawaiian Community | Thinking Locally

Pingback: Five Women’s Dormitories in 1929 Honolulu | Thinking Locally