Why do these girls prefer to work in homes when so much of the campus activities and events must be sacrificed? Why must they work? Why do they work? Are there no other choices? . . . All these girls needed financial support in order that they may have an education, a higher education (Anon., “College Working Girls’ Place in Society,” likely 1930s, Box A-1).

Most of the young women working as maids were Nisei Japanese and from large plantation families who couldn’t afford to support their children through college. These young women, particularly those at UH in the 1930s, knew that they had been fortunate to complete high school. RASRL writers often commented that many families, sometimes even their own, believed educating girls was a waste of resources, since upon marriage, girls were expected to leave their families and become part of their husbands’ economic units.

These young women were ambitious, determined; they had pluck. Although the hours could be long and some mistresses fickle and demanding, many relished the autonomy and independence they had living away from home and earning their way through college. But living with families brought obligations and living with family friends, close supervision and reports back to their parents.

Their time for co-curricular activity may have been circumscribed by their duties to their mistresses and families, but they could occasionally attend an event, particularly dances, an activity many Japanese parents not only frowned upon but forbade

The Japanese are yet of the old type and do not understand the social customs of the western world. It is hard for the girl to “skip out” to social functions and to enjoy herself whereas if she was working she has no such worry of pleasing and explaining to the guardian who seldom understands wholly why a girl must stay out until midnight to dance . . . She is her own boss [Anon., “College…”).

During the 1930s UH students found work as maids through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), which was created in 1932, and through the National Youth Administration (NYA), which operated from 1935 to 1939 as part of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (WPA).

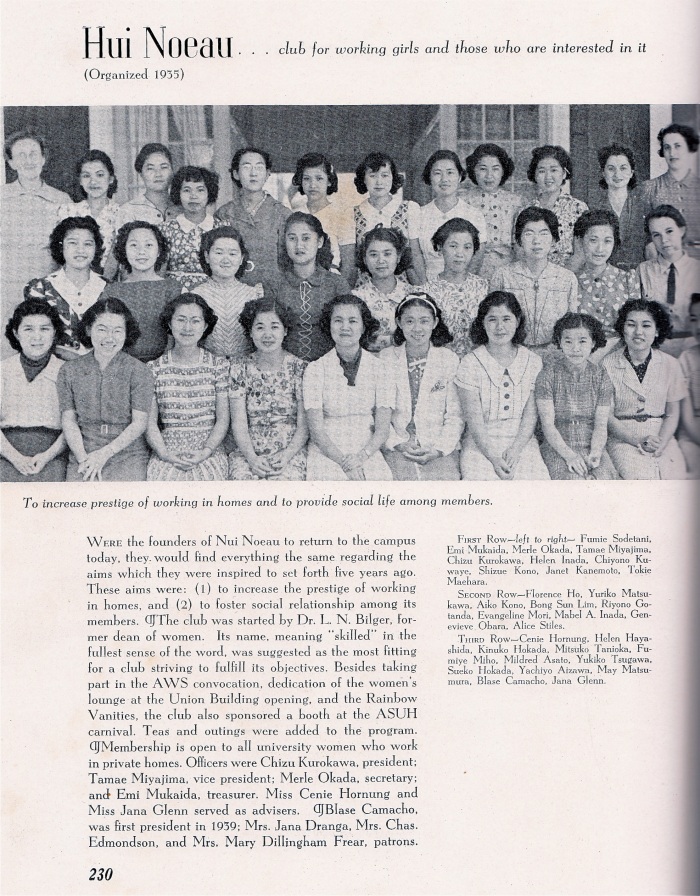

In 1935, to increase “the prestige of working in homes and to foster social relationships among its members” (Ka Palapala, 1939, p. 230), Dr. Leonora N. Bilger, faculty member in the Chemistry Department and Dean of Women, founded a club “for all University women who work in private homes.” Originally named the University Maids Club, the club was later renamed Hui Noeau at the members’ request. Its new name, “meaning ‘skilled’ in the fullest sense of the word, was suggested as the most fitting for a club striving to fulfill its objectives.” This new generation of workers in private homes saw themselves and wanted others to see them not as servile but as skilled workers.

According to the UH Placement Bureau, these young women received room, board, and a monthly salary of $20 (E.H. & H. K. , “ Sociological Study of Housemaids,” 1936, Box A-2).

Being a maid also offered on-the-job learning. Women who wished to be teachers found the work useful. They interacted with English speakers, had access to Haole employers’ magazines, newspapers, and other publications useful to their schoolwork. They conversed with mistresses of the house, learned to appreciate and understand “occidental ways” and saw how their “own race’s habits” compared to Haole’s (E.H. & H.K.).

Being a maid also offered on-the-job learning. Women who wished to be teachers found the work useful. They interacted with English speakers, had access to Haole employers’ magazines, newspapers, and other publications useful to their schoolwork. They conversed with mistresses of the house, learned to appreciate and understand “occidental ways” and saw how their “own race’s habits” compared to Haole’s (E.H. & H.K.).

The queer thing is that I sense a feeling . . . of superiority existing among the working girls towards those who do not work . . . . This complex lies in her ability to manage and understand haole life better than one who has not had much contact with haoles . . . and [they] have an advantage over girls who have had only contacts within her own racial group . . . . Once or twice I have heard remarks [from those not working] about their wanting to try working outside of their own homes … (Anon., “College…”).

In 1947 UH experienced a post-war boom in UH enrollment (Report of the President, 1946-47, p. 15) , while O‘ahu was dealing with a severe housing shortage. Many students had left home assuming that they could find a place to live while attending the University but were caught short. On-campus housing was limited and expensive at $75 a month, and rooms at off-campus dormitories or boarding houses were hard to come by. The University Placement Service sometimes “solved the problem” by helping University women find employment as live-in maids (A. H., “The Social Relationship of a Haole Family and Two Sisters,” 1947, Hormann Box 6).

When I first made plans to attend the University of Hawaii, I did not dream that the housing situation would be my outstanding problem. Probably many “[neighbor] island kids” like myself did not realize that too, but have found out through experience how bad it is. Like many others, I decided to combat the housing problem by exchanging my services for room and board. Nine months have elapsed since then and I have already lived in two households. The first residence was with a well-to-do Chinese family in Kaimuki … (M. K. M. “Mistress and Maid,” 1947, Hormann Box 6).

The above writer, showing an unusual degree of self-advocacy, went back to the Placement office to complain about the Chinese family and was then referred to a Haole family with a mistress who was well educated and coordinated the family’s dinner parties with the writer so as not to interfere with her studying for exams.

Frequently RASRL writers commented that Asian mistresses expected more from them than Haole ones who were more lenient and sympathetic. By the end of her senior year in high school, one writer was an experienced maid; she had served four different families, three “oriental” and one White. She had found Haole employers more lenient and sympathetic than “orientals” who expected much hard work and respect. One Asian mistress had added more working hours than originally agreed upon, found more for the writer to do when she had finished her assigned work, taken up her time on her day off, changed her day off, and expected her to stay until midnight to do the dishes after guests had left (D.Y., “Job Relations: Relationship between Mistress and Maid,” 1947, Hormann Box 6).

In one poignant passage, this writer, while working as a maid during her high school years, became painfully conscious of class differences:

I remember how shocked the mistress was when she saw me eating burnt rice which they were going to throw away. She thought I was nuts but I was really unconsciously following my father’s food conserving idea which was in his mores. … But then, I was too young to know anything about different mores and folkways so I went about feeling inferior, thinking of how dumb and clumsy I really was. Therefore, if I could help it, I tried not to ask questions so I wouldn’t have to feel dumb (D.Y., “Job Relations”).

Others with a strong sense of pride would have preferred work other than that of being a maid:

Returning home from school the first day, Mrs. Jones asked if she may see my class schedule. She wished to know the days I would be out early from school. It is rather selfish of her to require a part-time worker to be home right after school is dismissed. … Maids are usually regarded as someone who is bound by common understanding to do the undesirable work in the household. Therefore, it would be quite useless to leave this family and work for another and then another, forever leading a gypsy-life, instead of trying to adjust yourself and control the situations with which you are faced. On the whole, I believe that the mistress and maid relationship is the least desirable of all other types of job relationships (K. S., “Human Relationship in a Job Situation: Mistress and Maid,” 1947, Hormann Box 6).

Not quite an epilogue

Every year, a girl from the senior [high school] class is selected by the Dean [of Girls], and to be “the one” is the hope of the majority of the girls. This job is a highly desired one for most girls because it offers a girl an opportunity to live with people of different backgrounds from herself, since only a Japanese girl is hired; another thing the job offers is a trip to the island of Hawaii; the close employer-employee relationship such a job calls for is an outstanding factor which lacks in many ordinary jobs.

This writer was nervous before leaving for Hawai‘i Island to start her job: “I believe any person who had not had previous intimate contact with Haoles will no doubt be faced with the same feelings I at that time was confronted with.”

She had been selected to be elderly Mrs. C—-‘s companion, which required her to groom the elderly woman before bed, including brushing her false teeth, and to read to her. The writer slept in the room with the woman and was on-call from 7:30 p.m. to 7:30 a.m.

What made the writer uncomfortable was the formality between her and her employer. But one day that ceased: “People began to refer to me as the ‘C—-‘s girl.’ Such a title gave me a feeling of being important” (R.O. “Human Relations in a Job Situation,” 1947, Hormann Box 6).

Please visit our companion website Local Citing where we feature several community studies form the RASRL Collection in the Mapping the Territory exhibit.

Pingback: Five Women’s Dormitories in 1929 Honolulu | Thinking Locally